Why is American public transit so bad? Part 1

The highway's jammed with broken heroes on a last chance power drive

K. in Boston asks: “Why does the USA have bad trains and public transit vs the rest of the world?”

This is a big topic, and it's something I brood over incessantly care about deeply, so I’m going to split it into a two-parter. First we’ll cover the dawn of the automobile age up to about 1945, then next week we’ll talk about the death of American rail in the postwar era, as well as prospects for the future.

Public transit in America sucks, yes, but that wasn’t always the case. Let's take a look at a mid-size average American city as it was in 1900, and compare it to today. Load up some Scott Joplin on Spotify, pop a straw boater on your head, and cast your mind back to the good old days when Coca-Cola still had cocaine in it:

In 1900, if you lived in Toledo, Ohio you could step outside your door and hop on an electric streetcar that would carry you anywhere you needed to go around town. Because sprawl didn't exist in 1900, you wouldn't ever be more than a few blocks away from a streetcar line. If you rode it down to the main train station, you could then buy a ticket to go basically anywhere you wanted in the United States or Canada (no passport checks at the border, btw). A dozen railroads ran through Toledo, with frequent express service to Chicago, Pittsburgh, Columbus, or Cleveland. Other railroad lines and local electric "interurban" lines could take you out to the suburbs or to any small or mid-size town in Ohio. All told, more than 100 passenger trains would pass through Toledo's stations every day, so you would have been spoiled for choice as to departure time and destination. There was no Amtrak: all of these different railroads were operated by private companies, and they were big business: railroads as a sector represented 2/3rds of the value of the entire US stock market. Nationwide, the 1,200 railroad companies had one million employees, and (other than boats) they were the only way to travel any significant distance: train travel was an inescapable part of life in America.

Streetcar in Toledo, Ohio, 1900

Nowadays it's safe to say that most residents of Toledo never travel by rail: 79% of Toledo workers drive to work alone, only 0.6% commute via public transit. The city now has bus service instead of streetcars, but there is no light rail, commuter rail, or interurban service for suburban commuters. Downtown Toledo still has an Amtrak station, and as of 2023 there are two trains passing westbound and two trains passing eastbound per day (one of which has the useful departure time of 3:15AM) on a single rail line going between Chicago and Cleveland. Four a day, vs. 100+ a century ago. There is no direct way to reach Cincinnati, Columbus, or any of the dozens of Ohio towns once connected to Toledo by rail. The trains that do come are usually delayed, the on-time performance for these Amtrak lines serving Toledo is about 28%. Even if your train does come on time, travelling to Chicago from Toledo by rail will be slower than driving, and more expensive, too. Sure, the modern inhabitants of Toledo have cars now, but there's a cost: 43,000 Americans are killed in car crashes each year (~200 rail passengers died in train crashes in 1900), a significant amount of the average household's income is spent on car ownership, the average person wastes 97 hours a year sitting in traffic, and nationwide an area equivalent to Rhode Island and Delaware combined is taken up by surface parking lots. To apply a quote from Abraham Lincoln, "Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid".

Ohio’s passenger rail network in 1890, and 2023.

I didn't choose Toledo because it was particularly special, although it did have the good fortune of sitting at the junction of several rail lines. But in the early 1900s, towns as small as Red Lick, Mississippi (pop: 70) had train stations with regular passenger service, and most mid-size or even small towns (Guthrie, Oklahoma, pop: 10,006) had an electric streetcar system. They might not have had, you know, voting rights, or like...penicillin, but Americans in 1900 had an extremely robust and widespread mass transit network that makes anything we have today look like utter trash by comparison.

And of course, it's not just the past we can compare ourselves to. Any American who has ventured beyond our shores knows that rail-based public transit is light-years ahead in other countries, even in places that are poorer and less-developed than America. China builds more miles of subway track in a year than New York City has built in the past century, and even the Russkies have a high speed train that will whisk you from Moscow to St. Petersburg at 155mph for $50 a head. For a country that prides itself on being (supposedly) the best at everything, we have accepted that this is something we suck at. Why is that? For the answer, we’ll have to go back to the origins of the car as a consumer product, and understand why it took off in America so much faster than in other countries.

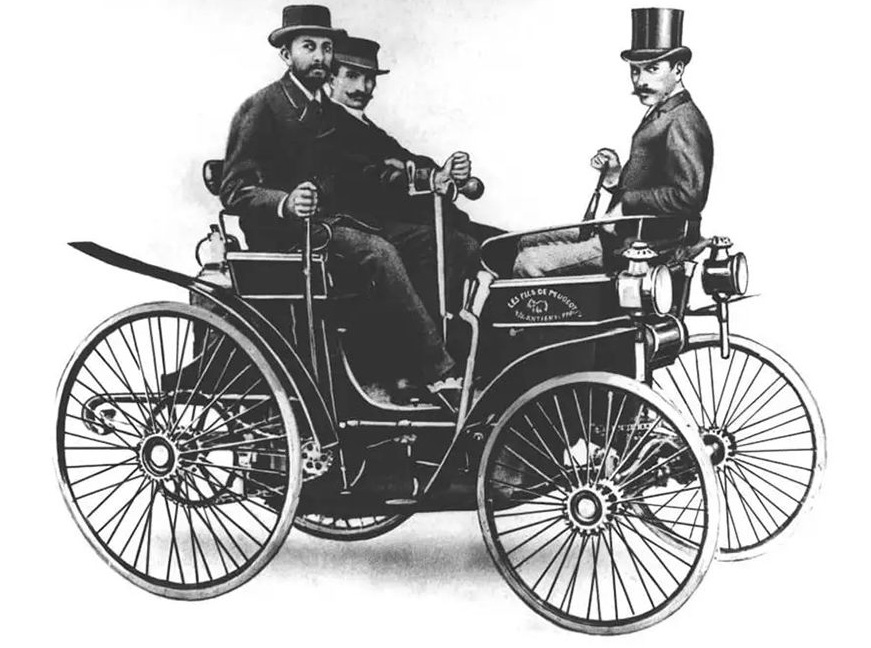

Self-propelled vehicles which we’d recognize as ancestors to the modern car date back to the late 19th century. They were powered by various methods: steam and battery power were the most common before gasoline caught on. They were slow, expensive, prone to breakdowns, and at the mercy of rough roads designed for horses. At the turn of the 20th century cars were a novelty, a rich man’s toy, and it seemed unlikely they’d ever reach the point of mass adoption: why bother with such a thing when you could take the train anywhere you wanted to go?

Hangin' out the passenger side of his best friend's steam-powered conveyance, trying to holla at me

But that era didn’t last: improved engineering and manufacturing techniques meant that Henry Ford’s 1908 Model T became the first truly mass-produced vehicle. Millions of cars began rolling off the assembly lines, and they were extremely affordable: in 1914 a Model T cost the equivalent of $13,500 in today’s money. Nowadays even a basic Hyundai compact costs more than that. While other industrialized countries also made cars, America took things to the next level: the massive domestic market, easy labour relations, and early adoption of mass-production techniques gave the Americans a huge advantage compared to European car companies. Ford’s industrial engineering was a complete paradigm shift: a Model T was rolling off the line every three minutes while the Europeans were still assembling bespoke vehicles by hand. American manufacturers could tap into a domestic market of 100 million consumers while a French manufacturer would face punishing import tariffs trying to sell in other European countries: there was no free-trade EU back then. As a result, by the mid-1920s America was making more than 4 million cars a year. Britain, France, Germany, and Italy combined were producing only half a million. It was no contest, and the mass adoption of cars began to rapidly transform American culture.

“Someone should write an erudite essay on the moral, physical, and esthetic effect of the Model T Ford on the American nation. Two generations of Americans knew more about the Ford coil than the clitoris, about the planetary system of gears than the solar system of stars… Most of the babies of the period were conceived in Model T Fords and not a few were born in them. The theory of the Anglo Saxon home became so warped that it never quite recovered.” - John Steinbeck

Traffic on Fifth Avenue, New York, 1911. Note the guy on the right about to get run over.

The Great Depression killed off a lot of manufacturers, but American producers could still benefit from economies of scale in a way that Europeans couldn’t. By the mid-30s the rate of car ownership had grown to 205 per 1,000, meaning 1 in 5 people now had a car. At the same time it was only 49 per 1,000 in France and 16 in Germany, and those were two of the most advanced industrialized countries. In the workers’ paradise of the Soviet Union it was 1.5 per 1,000. At this stage of history (even during the Great Depression) in terms of income, nutrition, affordability of consumer goods, and overall quality of life, a (white, male) American worker’s standard of living was much much higher than his counterpart in Milan, Hamburg, or Kharkiv, and his basic Ford or Chevrolet was an unattainable dream in Europe.

So this is where things stood on the eve of the Second World War: Americans had more cars than anyone else, and as such US rail had already declined by about half in terms of passenger-miles carried per year from the peak in 1920. Some of this was due to the Great Depression, but a lot of it was due to the Model T. Elsewhere, cars didn’t pose a serious threat to rail transportation yet. Despite the showy investment in Hitler’s Autobahn and Mussolini’s Autostrada, those highway systems were basically empty. Yes, Hitler promoted the VW Beetle as the “People’s Car,” but the whole thing was basically a PR stunt to show how great life was in the Reich: German workers were encouraged to put down deposits, but not a single Beetle was sold to the public until 1946. So while an American in 1939 might “motor” to work, city-dwelling Europeans still took the train or streetcar: there was no sense that mass transit was going into decline.

At this stage, many of the American streetcar companies started to go out of business. You might think this was due to competition with cars, free market and all that, but it was also due to a massive conspiracy known as the Streetcar Swindle. Now generally, I don’t believe conspiracy theories, but this one is a true story. Starting in the 30s, General Motors, Firestone Tires, and Standard Oil created a holding company with the object of buying up electric streetcar systems across the United States. The company acquired the transit systems in 44 cities ranging from Los Angeles to Lincoln, Nebraska, and then deliberately scrapped the streetcars so people would have no alternative but to buy cars (or use buses, which these companies could also profit from). The participating companies were convicted for antitrust conspiracy in 1949, GM was fined the equivalent of $50k in modern dollars (ouch), but by then it was too late: the streetcars had been sent to the junkyard and many of the affected towns would never have rail-based transit ever again.

Los Angeles streetcars in the junkyard, victims of the GM streetcar conspiracy. Today only 5% of LA residents use public transit to commute, and the average Angeleno spends more than 100 hours a year stuck in traffic.

After WW2, several things happened that gutted the viability of rail-based transportation. There was a major housing crisis across the country since basically no new homes had been built during the Great Depression and the war. Defense industry workers streamed into cities that were hubs for war production and for lack of housing they often had to double up (or triple up) in shared rooms in poorly-maintained older homes. Deferred maintenance added up after 16 years of Depression and wartime rationing, so everything was in crap condition. To be sure, there was a worse housing crisis in Europe and Japan, since prospective homeowners there could only choose from “pile of charred bricks,” or “pile of ash (including mixed human remains)”. But during the rebuilding phase the old street grid was adhered to more or less (add a park here or a statue of Comrade Stalin there), and cities were rebuilt at the same level of pre-war density, or even higher density since hideous socialist concrete high-rises became the order of the day. In America, the opposite happened: people fled the un-bombed yet decrepit cities and moved out to newly built car-dependent suburbs.

Well, some people did. The pale-looking sort of people. Mayonnaise-Americans, I hear they prefer to be called.

And here’s where things get nasty and quite depressing, but we’ll leave that for next week.

If you have a question or topic you want me to write about next, email distilledhistory@substack.com